A Patient's Guide to Osteoarthritis of the Wrist Joint

Introduction

Degeneration in a joint means the joint surfaces are starting to break down over time. The term degenerative arthritis is used by doctors to describe a condition where a joint wears out, usually over a period of many years. Some medical professionals call the condition osteoarthritis. Others use the term degenerative arthrosis. They prefer arthrosis because the term arthritis means inflammation. Degeneration by itself doesn't always cause inflammation in the tissues of the joint. Still, these terms are generally used to mean the same thing.

This document will help you understand

- how osteoarthritis of the wrist develops

- what your doctor will do to diagnose it

- what can be done to ease the pain and regain wrist movement

Anatomy

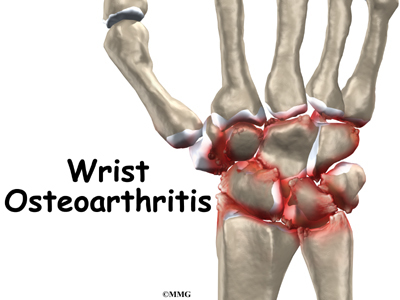

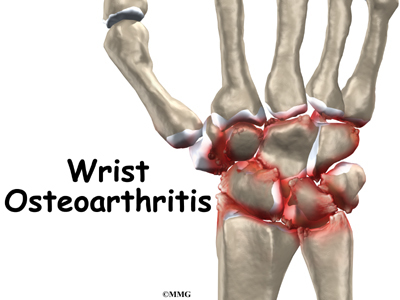

What changes does osteoarthritis cause in the wrist joint?

The anatomy of the wrist joint is extremely complex, probably the most complex of all the joints in the body. The wrist is actually a collection of many joints and many bones. These joints and bones let us use our hands in many ways. The wrist must be extremely mobile to give our hands a full range of motion. At the same time, the wrist must provide the strength for heavy gripping.

The wrist is made up of eight separate small bones, called the carpal bones. The carpal bones connect the two bones of the forearm, the radius and the ulna, to the bones of the hand. The metacarpal bones are the long bones that lie underneath the palm. The metacarpals attach to the phalanges, which are the bones in the fingers and thumb.

One reason that the wrist is so complicated is because every small bone forms a joint with the bone next to it. This means that what we call the wrist joint is actually made up of many small joints. Ligaments connect all the small bones to each other. Ligaments also connect the bones of the wrist with the radius, ulna, and metacarpal bones.

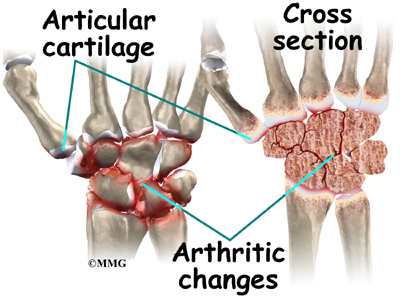

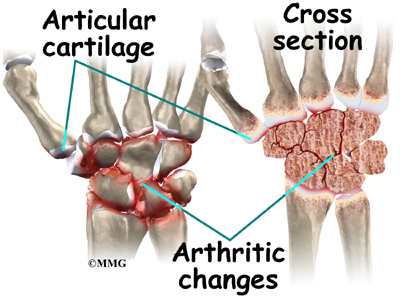

Articular cartilage is the smooth, rubbery material that covers the bone surfaces in most joints. It protects the bone ends from friction when they rub together as the joint moves. Articular cartilage also acts sort of like a shock absorber. Damage to the articular cartilage eventually leads to osteoarthritis.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Wrist Anatomy

Causes

How did I develop arthritis in my wrist?

Many wrist injuries, such as fractures and sprains, heal fairly easily. However, they can lead to problems much later in life. The injury changes the anatomy of the wrist just enough so that the parts no longer work smoothly together. The changes from the injury cause a lot of wear and tear on the wrist joint. Over time, this wear and tear degenerates the tissues of the joint, leading to wrist osteoarthritis. Doctors may also call this type of degeneration posttraumatic arthritis.

A bad sprain or fracture can actually damage the articular cartilage. The cartilage can also be bruised when too much pressure is put on the cartilage surface. The cartilage surface may not look any different. The injury often doesn't show up until months later.

Sometimes the damage to the cartilage is severe. Pieces of the cartilage can actually be ripped away from the bone. These pieces do not grow back. Usually they must be surgically removed. If the pieces aren't removed, they may float around in the joint, causing it to catch. They an also cause a lot of pain and do more damage to the joint surfaces.

Your body does not do a good job of repairing these holes in the cartilage surface. The holes fill up with scar tissue. Scar tissue is not as slick or rubbery as the articular cartilage.

Any kind of injury to the wrist joint can alter how the joint works. After a wrist fracture, the bone fragments may heal slightly differently. Ligament damage results in an unstable joint. Any time an injury changes the way the joint moves, even if the change is very subtle, the forces on the articular cartilage increase. It's just like a machine; if the mechanism is out of balance, it wears out faster.

Over many years, this imbalance in joint mechanics can damage the articular cartilage. Since articular cartilage cannot heal itself very well, the damage adds up. Finally, the joint can no longer compensate for the damage, and your wrist begins to hurt.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Ligament Injuries of the Wrist

Symptoms

What problems does arthritis of the wrist cause?

Pain is the main symptom of osteoarthritis of any joint. At first, the pain comes only with activity. Most of the time the pain lessens while doing the activity, but after stopping the activity the pain and stiffness increase. As the condition worsens, you may feel pain even when resting. The pain may interfere with sleep.

The wrist joints may be swollen. Your wrist may fill with fluid and feel tight, especially after use. When all the articular cartilage is worn off the joint surface, you may notice a squeaking sound when you move your wrist. Doctors call this creaking crepitus.

Osteoarthritis eventually affects the wrist's motion. The wrist joint becomes stiff. Certain motions become painful. You may not be able to trust the joint when you lift objects in certain positions. This is because a pain reflex freezes the muscles when a joint is put in a position that causes pain. This happens without warning, and you can end up dropping whatever is in your hand.

Diagnosis

What tests will my doctor do?

The diagnosis of wrist osteoarthritis begins with a medical history. Your doctor will ask questions about your pain, how it interferes with your daily life, and whether anyone in your family has had similar problems. It is especially important to tell your doctor the details of any wrist injuries you've had, even if they happened many years ago.

Your doctor will then physically examine your wrist joint, and possibly other joints in your body. It may hurt when your doctor moves or probes your sore wrist. But it is important that your doctor sees how your wrist moves, how it is aligned, and exactly where it hurts.

You will probably need to have X-rays taken. X-rays are usually the best way to see what is happening with your bones. X-rays can help your doctor assess the damage and track how your joint changes over time. X-rays can also help your doctor estimate how much articular cartilage is left.

Your doctor may order blood tests if there is any question about the cause of your arthritis. Blood tests can show certain systemic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Treatment

What can be done to get rid of my pain?

Nonsurgical Treatment

In almost all cases, doctors try nonsurgical treatments first. Surgery is usually not considered until it has become impossible to control your symptoms.

The goal of nonsurgical treatment is to help you manage your pain and use your wrist without causing more harm. Your doctor may recommend nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin and ibuprofen, to help control swelling and pain. Other treatments, such as heat, may also be used to control your pain.

Rehabilitation services, such as physical and occupational therapy, have a critical role in the treatment plan for wrist joint arthritis. The main goal of therapy is to help you learn how to control symptoms and maximize the health of your wrist. You'll learn ways to calm your pain and symptoms. You may use rest, heat, or topical rubs.

A special brace may help support the wrist and reduce your pain during activity. Range-of-motion and stretching exercises can improve your wrist motion. Strengthening exercises for the arm and hand help steady the wrist and protect the joint from shock and stress. Your therapist will give you tips on how to get your tasks done with less strain on the joint.

To get rid of your pain, you may also need to limit your activities. You may even need to change jobs, if your work requires heavy, repetitive motions with the hand and wrist.

An injection of cortisone (a powerful anti-inflammatory medication) into the joint can give temporary relief. It can very effectively relieve pain and swelling. Its effects are temporary, usually lasting several weeks to months. There is a small risk of infection with any injection into the joint, and cortisone injections are no exception.

Surgery

If the pain becomes unmanageable, you may need to consider surgery. There is no single surgery for arthritis of the wrist. The wrist is complex, and many different injuries can lead to arthritis. As a result, there are many possible surgical procedures for treating a painful wrist joint. Which one is right for you depends on your underlying problem, how much of the wrist joint is involved, and how you need to use your wrist.

In some cases, people with arthritis of the wrist have already had wrist surgery after an earlier injury. This past surgery may have repaired broken bones or stitched together torn ligaments. The surgery at least may have helped delay osteoarthritis in the wrist. A previous surgery can be a factor in deciding which procedure is best for you.

If the arthritis involves only one or two of the small carpal bones of the wrist, you may undergo a special procedure that focuses on only those bones. If you have advanced osteoarthritis that affects most of the wrist, your doctor will probably suggest a wrist fusion or an artificial wrist joint.

When the wrist joint becomes so painful that it is difficult to grip or move the wrist, your doctor may recommend fusing the wrist joint. A wrist fusion is sometimes called an arthrodesis of the wrist. The goal of a wrist fusion is to get the radius bone in the forearm to grow together, or fuse, into one long bone with the carpal bones of the wrist and the metacarpals of the hand. A wrist fusion is a challenging operation. A fusion of most other joints involves only two or three bones. Wrist fusion involves getting 12 or 13 bones to grow together. But wrist fusion is usually successful in relieving wrist pain.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Wrist Fusion

A wrist fusion gets rid of pain in the wrist and restores strength, but it isn't a great choice for someone who needs to move the wrist more freely. Patients who have arthritis in both wrists don't usually get two wrist fusions. That would make it very difficult to do everyday activities such as turning door knobs and taking care of basic hygiene.

Patients who have wrist arthritis due to systemic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, are much more likely to have arthritis in both wrists. These patients probably don't need wrist strength as much as good range of motion. They would probably benefit from at least one wrist joint replacement. In some cases, surgeons fuse one wrist for strength and replace the other wrist with an artificial joint for motion.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Artificial Joint Replacement of the Wrist

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

If you don't need surgery, you will probably work with a physical or occupational therapist. Range-of-motion exercises for the wrist should be started as pain eases. A program of strengthening follows. Eventually you will be doing strength exercises for the arm and hand. Dexterity and fine motor exercises are used to get your hand moving smoothly. You'll be given tips on keeping your symptoms under control. You will probably progress to a home program within four to six weeks.

After Surgery

Your hand and wrist will be bandaged with a well-padded dressing and a splint for support after surgery. Physical or occupational therapy sessions may be needed for up to three months after surgery. The first few treatment sessions will focus on controlling the pain and swelling after surgery. You will then begin to do exercises that help strengthen and stabilize the muscles around the wrist joint. You will do other exercises to improve the fine motor control and dexterity of your hand. Your therapist will give you tips on ways to do your activities without straining the wrist joint.

|